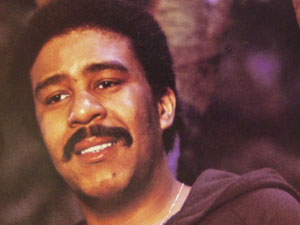

Richard Pryor

Died Saturday, of a heart attack. He was 65.

Pryor was not only the greatest American stand-up comic of his, or any other, generation -- he was a dramatist, a documentarian, a tortured soul who threw all the madness and misery he'd seen and experienced into his characters and public confessions. In his prime, Pryor blew past his comedy peers, such as they were, and operated on a level all his own. Stand up served as a release, but such a limited form could not fully transmit his eloquent fury.

Pryor's main nerve was intensity. I've never seen a comic so directly tapped into raw emotion as was Pryor. Even when he laughed or kidded around, there was danger. You saw it in his eyes, a don't-fuck-with-me stare that sliced through anyone who met his gaze. (I recall Pryor taunting Barbara Walters during an interview, asking her to say "nigger" to his face, assuring her that the word comes easily to any white person. When Walters replied that she could never utter such a thing, Pryor smiled and said, "Sure you can.")

Pryor may not have been the most muscular of men, but you didn't want to piss him off. Stories abound: his emptying a .357 Magnum into one wife's car after an argument; pressing the same .357 to the head of another wife, chasing her out of the house; grabbing a cognac bottle and threatening to bash Michael O'Donoghue in the head after O'Donoghue told a joke Pryor thought was racist (though it was a spoof of George Wallace's racism). But for all that's been revealed, there must have been countless other incidents, given Pryor's history, his anger, his determination that things be done his way.

Cocaine played a role as well, for you cannot pour that kind of fuel on a fiery persona like Pryor's and expect no reaction, self-immolation through free basing and his first heart attack being two serious, life-threatening examples.

Yet for all his intense volatility, Pryor also exhibited a soft sweet side, the eye of his emotional storm. Friends and loved ones have spoken of it, and he was generous to younger comics in whom he saw possibility and promise. Look at the line up of his 1977 NBC show: Sandra Bernhard, Robin Williams, Marsha Warfield, Tim Reid, Paul Mooney, Vic Dunlop, Jimmy Martinez, Argus Hamilton, and John Witherspoon -- all unknowns who later experienced varying degrees of success. Not many established comics would surround themselves with young talent of that caliber and risk being upstaged. But Pryor, for all his mania, knew how good he was, and naturally he demanded a first-rate supporting cast. Unfortunately, "The Richard Pryor Show" came and went in just over month. As Pryor himself explained:

"When I committed to do a 10-week comedy variety series on NBC, I thought I could do something significant. I saw only the possibilities of TV as a way of communicating . . . But the reality of what the network censors allowed on prime time undercut all my enthusiasm. Not only were we pitted against 'Happy Days' and 'Laverne & Shirley,' the two top-rated shows, but the network censors thwarted me from the git-go. Because I didn't want to sell out completely, I got NBC to agree to reduce the number of shows from 10 to 4, the less the better.

"We still managed to deliver an exciting, surprising and provocative show. This show was no vanilla milkshake. It was poignant. I am proud of the effort."

Unlike most of his films, Pryor's short-lived TV series was perhaps the best creative extension of his stage act, comedy blending with drama, absurdity, strangeness and commentary. Pryor's pulling back was prescient on his part, as I cannot fathom NBC airing 10 weeks of that type of programming in prime time.

Still, just think about it -- NBC, which was undergoing a ratings slump at the time, had Richard Pryor under contract and couldn't get that right. When you watch those four shows, you can't help but wonder where Pryor and company might have taken a longer series once they had their broadcast footing. A tremendous waste of talent and intelligence.

In a freewheeling, unaired monologue that appears on the show's DVD box set, Pryor, speaking through Mudbone, an old man who spins tall tales while spitting into a rusty coffee can, let NBC have it, telling production assistants who ask him to tone it down and start over, to fuck off, adding that he doesn't give a shit about what TV needs or wants. Wisely, they back off, and Pryor launches into a hilarious, profane half-hour bit about racist bosses and a crazy voodoo priestess.

While Pryor became enormously successful with mainstream outings like "Silver Streak," "Which Way Is Up?" and "Stir Crazy," it is in Paul Schrader's 1978 film "Blue Collar" where his best acting can be seen.

Pryor, Harvey Keitel and Yaphet Kotto play auto workers who are stretched to the limit financially, and are manipulated and pitted against each other by both the car company and the corrupt local union. It's a dark and ultimately depressing film, and it remains one of the starkest dramatic examinations of racism, capitalism and the struggles of working people seen in modern cinema. And like his aborted TV show, one can only imagine what Pryor might have achieved as an actor had he further explored this area.

Ultimately, it is Pryor's stand-up that will serve as his legacy. In the days before HBO, the only way you could experience uncensored comedy was on record, and Pryor's best three -- "That Nigger's Crazy," "Is It Something I Said?" and "Bicentennial Nigger," remain incredibly funny.

When I was 15/16-years-old, my father and his brother used to play these albums in our basement, the sound of their loud constant laughter coming up the stairs along with the scent of pungent weed. I was never invited to join in, for obvious reasons, but I did envy their enjoyment and unbridled fun. When no one was around, I'd grab the albums and listen to Pryor's routines in my bedroom, my young mind opening to language and images that took me repeated listenings to fully comprehend. And though by this point in time I'd decided on a career in comedy, I knew that I could never remotely approach what Pryor was doing, and I doubted that anyone ever could. To date, none have.

Pryor said that no matter how hard he tried, he could never escape the darkness that engulfed him. But by channeling this darkness into his performances, Richard Pryor exposed some light, that segment of the human heart where the sadness of our existence is upended, if only briefly, to show us and others the promise of love and tenderness and the possibility of emotional survival. A tough, thankless gig that Pryor took on point blank, and that in the end, along with everything else, broke him.

I can't think of many comics or performers of any kind who would attempt to lift that kind of weight, much less do so as brilliantly as Pryor. He was the one and only. Let's remember him with a smile.

<< Home