Pointless

About half way through "Wild Man Blues," the docu about Woody Allen's jazz band touring Europe, I'd seen enough, ejected the disc. I've long been a big Allen fan, from his 60s stand-up to the many fluctuations of his film career, but the sourness and misanthropy he displayed in "Wild" was too much for me to take. I certainly hope he's not as bitter and petty as he's portrayed in that film; yet, when you look at some of his darker efforts and note the consistent bleak strands within, Allen probably is like that in life (reflected also in a Vanity Fair profile from Dec. '05). How else could he so accurately and artfully translate this to film? For him, a half-empty glass is unreasonably optimistic.

Watching "Match Point" reinforced this perception, though not unpleasantly so. When Allen is on his game, he sweeps you right into the narrative and smoothly carries you to its end. This is not to say that it's a completely comfortable ride -- the delusion, hypocrisy and cynicism of his characters would immediately repel any reasonable or sensitive person were they flesh; but as flickering images, they are irresistible to observe. And that Allen uses contemporary London as his location, a new backdrop for him, lends "Match Point" a certain freshness that would be missing were the film set in Manhattan. No one shoots New York like Allen, but he's pretty much wrung that great city out, so it's nice to see his story unfold elsewhere.

I won't reveal much of "Match Point" -- if you've seen it, you don't need my explication; if you haven't, it's now out on DVD, so grab one and watch. It's one of Allen's better films, though like much of his recent work, elements from earlier efforts appear, in this case, "Crimes and Misdemeanors," which to me is Allen's masterpiece. Characters are made to pay for the bad choices they've made, and in order to extricate themselves from potentially ruinous consequences, they choose to behave even worse. In Allen's world, one can do something or be part of something horrid, and while detection always looms, they usually get away with it, thanks to chance and luck. And that's what's so horrifying about these scenarios: the getting away with it. We know that people get away with murder in real life (when they're not simply celebrated for killing others), but it requires fiction to really make us understand the full implication of this, something Allen has down. There's no relief for the supposedly Not Guilty, not if they have any conscience or sense of personal morality. They escape jail only to be imprisoned in their mind. In "Crimes and Misdemeanors," Martin Landau's character rattles the bars in his soul to the point of a complete emotional breakdown, only to find, one sunny morning, that the bars are melting away. Distance from his crime allows rationalization to soothe his battered psyche, and in time he's free once again. Not only does he get away with it, he becomes happier and financially prospers, perhaps the most frightening development of all.

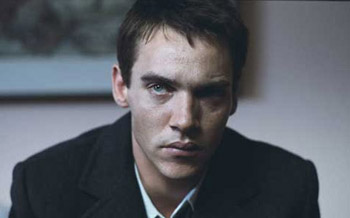

In "Match Point," Jonathan Rhys-Meyers isn't allowed Landau's luxury. His amoral ambition and appetite not only land him in a mental prison he cannot escape, but a physical one that he refuses to flee, namely, the wealthy family he marries into. By film's end, you see the suffocation in his eyes. He knows he's going to prosper, safely tied to big money and class privilege, but he sure as hell doesn't look happier. Indeed, he looks worse. He's well aware of the crime he's committed, and for him there's no personal justification, just emotional repression, and even that appears shaky. "Match Point" is less horrifying than "Crimes and Misdemeanors," but it lingers in the mind, reminding you that perhaps everything is random, morality is a delusion, and that the only point to life is grabbing what you can, any way you can, before the final night falls.

Many seem comfortable with this. Woody Allen, resigned to it. Me, saddened if it is so.

<< Home